Listen to Anne Eaton read her letter to her father; read it below.

Anne Eaton wrote her father a letter describing the participants of the 1957 conference. Cyrus Eaton had just started courting her and had asked her to be his hostess.

July 12, 1957

Pugwash

Nova Scotia

Dear Judge

We have met the Soviets and they are ours. Four of them invaded by air from Moscow via Montreal looking as tired as anyone would after an 18-hour trip with a 7-hourr time change.

July 12, 1957

Pugwash

Nova Scotia

Dear Judge

We have met the Soviets and they are ours. Four of them invaded by air from Moscow via Montreal looking as tired as anyone would after an 18-hour trip with a 7-hourr time change.

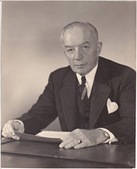

Cyrus Eaton hosted the 1957 conferences sporting an Homburg

Cyrus and Anne take guests out on the water.

Professor Dmitri Skobelzyn is eldest, a tall, white-haired, distinguished looking man with the only Homburg in Pugwash beside Cyrus’s. The hats are the same size and shade of grey, hence are regularly claimed for the wrong ideology from hooks in the vestibule of an old Masonic Hall where the meetings are held. Skobeltzyn, Director of the Lebedev Institute of Physics in Moscow, was born in Leningrad (which he still calls St. Petersburg) where he attended the same high school as a U.S. participant, Eugene Rabinowitch, the editor of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists and professor at the University of Illinois. Skobeltzyn is not a Communist Party member. He is a pioneer in cosmic ray research and represented the Soviets on the scientific advisory group during the U.N. atomic energy control negotiations from 1946 to 1948. He speaks a bit of English, more French.

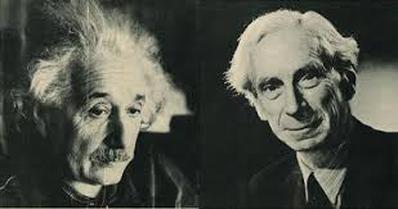

Dmitri Skobelzyn with Homburg

Academician (I should say instead of Professor) Alexander Topchiev is a very different type: short and so stocky that with the current style of wide trouser legs for Soviets he gives the impression of an upright rectangular block. His eyeglasses slip a bit, though only one ear at a time ‘can be hooked onto, and he has a deceptively severe look, rather beetle-browed. He is Secretary General of the Soviet Academy of Sciences, an organic chemist. He attended a London conference two years ago (when all this began) just before the Geneva Conferences on Peacetime Uses of Atomic Energy. Bertrand Russell was responsible for pushing that London meeting with the Parliamentary Association for World Government. It was the first attempt at international cooperation of scientists after Hiroshima and was small, not representative, it‘s said, with more non-scientists than scientists. Nothing much came of it until now, but it, like this, resulted from the Russell-Einstein Appeal to scientists to consider the hazards of nuclear war.

The third Soviet Academician Aleksandr Kuzin, went to London, too. He is a biophysicist, a fairly perilous discipline in the USSR, I'm told, where genes are expected to follow certain rather bizarre rules of dialectic materialism. Kuzin sports a small, well-tended moustache, wears a black beret and manages to look a bit stylish, floppy trouser cuffs notwithstanding.

The interpreter’s name is Vladimir Pavlichenko. He is young, plump and he smiles, particularly when he shows snapshots of his pretty wife and two small children. He is Topchiev’s secretary.

On arrival they joined the rest of us. I'll give the whole cast in due course-in the big living room of this white frame house built in 1800 by Cyrus's ship -builder great uncle. [Note Cyrus bought the Lodge in 1929 from the Pineo family.] It overlooks the Northumberland Strait. I'll describe placid Pugwash later. What a spot for a conference, nothing to do but think. (“Think or Swim” is a motto offered. been marvelously well received by the English speaking but suffers somewhat in translation.)

The Soviets drank a cautious ginger ale before we went down a grass slope to dinner in the dining room, an all-white converted lobster factory on a wharf. It can seat 50 at an arresting collection of black, antique tables and chairs. White uniformed local ladies act as waitresses, drilled in the niceties of service by an Admirable Crichton of a French Nova Scotian, Ramon (pronounced Ramon) Bourque. He is loaned to Cyrus to be major domo of these affairs. by the Canadian National R.R. which also permits three private cars to park alongside the Victorian red brick station in town: extra-and palatial-accommodations. By a gloriously incongruous chance the Soviets are in the one Fi Fi Widener.

The interpreter’s name is Vladimir Pavlichenko. He is young, plump and he smiles, particularly when he shows snapshots of his pretty wife and two small children. He is Topchiev’s secretary.

On arrival they joined the rest of us. I'll give the whole cast in due course-in the big living room of this white frame house built in 1800 by Cyrus's ship -builder great uncle. [Note Cyrus bought the Lodge in 1929 from the Pineo family.] It overlooks the Northumberland Strait. I'll describe placid Pugwash later. What a spot for a conference, nothing to do but think. (“Think or Swim” is a motto offered. been marvelously well received by the English speaking but suffers somewhat in translation.)

The Soviets drank a cautious ginger ale before we went down a grass slope to dinner in the dining room, an all-white converted lobster factory on a wharf. It can seat 50 at an arresting collection of black, antique tables and chairs. White uniformed local ladies act as waitresses, drilled in the niceties of service by an Admirable Crichton of a French Nova Scotian, Ramon (pronounced Ramon) Bourque. He is loaned to Cyrus to be major domo of these affairs. by the Canadian National R.R. which also permits three private cars to park alongside the Victorian red brick station in town: extra-and palatial-accommodations. By a gloriously incongruous chance the Soviets are in the one Fi Fi Widener.

Croquet matches helped thaw the ice.

Croquet matches helped thaw the ice.

Academician Topchiev seized my wheel-chair and pushed me down the fairly rough terrain at a speed I can truthfully call breathtaking. Pavlichenko ran alongside, smiling. After dinner Topchiev asked if Cyrus and I would play croquet with him and Kuzin. Of course we would, so Topchiev seized me again and we went back up the hill at the speed described above. Since Pavlichenko stayed behind to interpret, the Academician and I were on our own, mute but smiling. He indicated that he and I were partners. We chose-and taught each other the words for mallets and balls. Soviet croquet rules are the same as ours, except they (an historical footnote of immense significance) hadn‘t heard of sending the opponents ball anywhere, once hit it. It's that business of putting your ball cheek by jowl with the and then, with foot on your own ball to hold it, smacking as hard as possible. When my partner hit Cyrus' ball I explained this Anglo Saxon move and urged sending Cyrus into the apple trees along the court. Lots of roots and rough grass. Topchiev wondered if this would be proper since it was his ball. I said that if he didn't snatch this chance for victory, I would never forgive him. He conferred with Kuzin whose heart, I felt, had not been in the game until he asked for and received permission to smoke. He accepted an American cigarette from me and I took one of his which was strong, unfiltered and aromatic enough to be a massive deterrent, to coin a phrase, to the mosquitoes as the game progressed.

Topchiev emerged from the conference grinning and knocked Cyrus' ball beyond the apple trees. We won. The Soviets kissed my hand, shook Cyrus' and we all wished each other good night. My Russian vocabulary is ball, mallet, wheelchair, thank you, you‘re welcome, good!, cigarette, match, lighter, mild, strong, hooray!, good night, light and sea. Also partner.

Topchiev emerged from the conference grinning and knocked Cyrus' ball beyond the apple trees. We won. The Soviets kissed my hand, shook Cyrus' and we all wished each other good night. My Russian vocabulary is ball, mallet, wheelchair, thank you, you‘re welcome, good!, cigarette, match, lighter, mild, strong, hooray!, good night, light and sea. Also partner.

Joseph Rotblat speaking

Joseph Rotblat speaking

By noon the next day all 24 men from 10 countries had arrived in response to the invitation from Bertrand Russell and several signers of the 1955 Russell-Einstein Appeal, several of whom are here. They were invited as individuals, not as delegates of anything, but include, for instance, the Chairman of the Federation of American Scientists, Paul Doty of Harvard, and Walter Selove of Pennsylvania who is head of the FAS Committee on Biological Dangers. Joseph Rotblat, a Polish-born physicist at the University of London (and a signer) is V.P. of the British Atomic Scientists Association. He and Cecil Powell, a Nobel Prize winner in physics from Bristol (who quotes Shakespeare and Hazlitt and other wisdoms with that soothingly civilized choice of word, time, point and voice) made the preparations for this meeting. Powell also signed the Appeal. The Soviet Academy chose the Soviet participants.

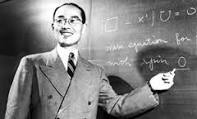

Hideki Yukawa,

Hideki Yukawa,

There are two more Nobel Prize Winners here: a physicist, Hideki Yukawa, from Tokyo University and a geneticist, Hermann Muller, from Indiana. All three signed the Appeal in 1955.

Leo Szilard addressing participants

Leo Szilard addressing participants

Leo Szilard had arrived days ago, minus his luggage. He is a roly-poly Hungarian-born genius who built the first atomic pile with Fermi at the University of Chicago where he is now professor of physics. He's been holed up at house across the street, dictating a scientific paper into a machine. One of the secretaries is laboring to transcribe it. His accent, recorded, is formidable even to me and the secretary, born in Germany, appealed to me for help. That neither of us understands the subject is no help.

Ramon Bourque tirelessly assisted all guests.

Ramon Bourque tirelessly assisted all guests.

Cyrus‘s sister, Eva Webb, is slightly stunned by this houseguest who announced that Nova Scotia should have an annual Festival of Lost Causes to celebrate the Empire loyalist deportation from the United States, the Bonnie Prince disaster, and the expulsion of Acadians. Since ancestors were Empire Loyalists from New York (the appropriated property was the corner of Broadway and Wall Street), and his mother was a Macpherson, and Eva is an ardent Nova Scotian, though she lives in Toronto, she has failed to see the humor of it. Not so Ramon Bourque whose Acadian ancestors sailed around a bit and then landed and stayed in Yarmouth.

Antonie Lacassagne

Antonie Lacassagne

There’s a marvelous, spare, elegant, 73-year-old Frenchman, Antoine Lacassagne, from du Radium, Paris. He worked with the Curies from the beginning. The Japanese Nobel Prize winner is accompanied by his nephew, a physicist named lwao Ogawa, and another physicist, Sin-itiro Tomonaga. Both are from Tokyo. With Professor Chou Pei Yuan, Vice Rector of Peking University, they are the East here. Professor Chou, a most urbane man who bows frequently, speaks perfect, soft, English and is as at home in Shakespeare as in his own literature. I find this considerably humbling. Yukawa speaks English, too.

Sir Mark Oliphant is third from left.

Sir Mark Oliphant is third from left.

There’s a Polish professor, J. Danysz from Warsaw; a ruddy Australian, Mark Oliphant, who directs a post-graduate research school in Canberra; a dear, delicate, elderly Viennese physicist, Hans Thirring, who presented, diffidently, his book The Theory of Relativity and Einstein Theory; and Victor Weisskopf of M.I.T., who was ?'s pupil in Vienna before the war.

The Americans have a grand Bostonian be reassured to know: David F. Cavers, Associate Dean of the Harvard Law School. Dr. Brock Chisholm, a psychiatrist from Victoria, B.C., and a former director of the World Health Organization, and another physicist from McGill, John Foster, represent Canada. Except that no one represents anything but himself.

The Americans have a grand Bostonian be reassured to know: David F. Cavers, Associate Dean of the Harvard Law School. Dr. Brock Chisholm, a psychiatrist from Victoria, B.C., and a former director of the World Health Organization, and another physicist from McGill, John Foster, represent Canada. Except that no one represents anything but himself.

I think described all but the supporting cast of assistants so that you can visualize their first encounter with each other in the big room overlooking the strait. It had the feel of a railroad station waiting room, full of silent strangers. Some, of course, knew each other; many were known to each other, had even corresponded, but the only real common denominator was Russell‘s invitation. So the gathering of scientists from both sides of both curtains for the first time since Hiroshima, to assess, in Russell's words, the hazards of the nuclear age, was absolutely still. For minutes.

Szilard began, “We find ourselves in a situation very like that between Athens and Sparta,” and he stopped to allow for the whispered translations. Yukawa told his nephew and the other young Japanese. They nodded. Pavlichenko explained to the Soviets and Danysz; they nodded. Lacassagne arched an eyebrow and looked pleased. Meanwhile Oliphant's John Bull face was beaming, and Chou registered amusement. Thirring nodded earnestly. The British and Canadians looked relieved, and the Americans, native and foreign born, relaxed. It was unanimous.

And it gratified this old classicist who never had a course in physics to find the common ground for scientists in that Greek vicious circle. Nobody identified Athens, naturally, but the conversation began. Only a Hungarian would have thought of it.

Szilard went on with his parallel and then reminisced. He went to Einstein with the news of the successful chain reaction because Einstein was such a friend of Elizabeth, the Belgian queen, and the Belgian Congo was Germany's source of uranium. Szilard wanted Einstein to urge Elizabeth to cut off that supply. If the chain reaction could be achieved in the United States by those refugees from Hitler's Europe, like Szilard, their less fortunate colleagues who were forced to work for Germany would have it soon-possibly already had. To Szilard the urgent matter was not making the bomt, but making sure that Germany didn‘t. Einstein went to Roosevelt with the news.

After the bomb went to production, Szilard spent all his time and money trying to persuade the United States not to use it. He suggested inviting the Japanese High Command to observe the bombing of an uninhabited Pacific Island to demonstrate what kind of monstrous thing it was. That would have been enough for surrender, he said. The United States, according to Szilard, decided against that course for fear the first bomb might not go off.

During this recitation I was acutely aware of my Japanese guests. All three are small-boned and delicate, with soft voices. They sat together so the Nobel Prize-winning elder could translate. The younger ones listened with a kind of stoic acceptance of their avoidable tragedy. (Not I. I had never heard this before.)

Their concern, though, however gently put, over further nuclear testing, like the Bikini Atoll one which injured their fishermen and put radioactive tuna on Japanese tables, is vivid. Tomonaga said, “Hiroshima was a tragedy, but anti-Americanism is not so strong as fear of the results in radioactivity from tests.” One committee here focuses on radiation hazards - from testing and from an all-out war. I’ll be interested to see if the testers agree with the tested-upon; everyone seems to be testing near the Japanese islands.

Szilard began, “We find ourselves in a situation very like that between Athens and Sparta,” and he stopped to allow for the whispered translations. Yukawa told his nephew and the other young Japanese. They nodded. Pavlichenko explained to the Soviets and Danysz; they nodded. Lacassagne arched an eyebrow and looked pleased. Meanwhile Oliphant's John Bull face was beaming, and Chou registered amusement. Thirring nodded earnestly. The British and Canadians looked relieved, and the Americans, native and foreign born, relaxed. It was unanimous.

And it gratified this old classicist who never had a course in physics to find the common ground for scientists in that Greek vicious circle. Nobody identified Athens, naturally, but the conversation began. Only a Hungarian would have thought of it.

Szilard went on with his parallel and then reminisced. He went to Einstein with the news of the successful chain reaction because Einstein was such a friend of Elizabeth, the Belgian queen, and the Belgian Congo was Germany's source of uranium. Szilard wanted Einstein to urge Elizabeth to cut off that supply. If the chain reaction could be achieved in the United States by those refugees from Hitler's Europe, like Szilard, their less fortunate colleagues who were forced to work for Germany would have it soon-possibly already had. To Szilard the urgent matter was not making the bomt, but making sure that Germany didn‘t. Einstein went to Roosevelt with the news.

After the bomb went to production, Szilard spent all his time and money trying to persuade the United States not to use it. He suggested inviting the Japanese High Command to observe the bombing of an uninhabited Pacific Island to demonstrate what kind of monstrous thing it was. That would have been enough for surrender, he said. The United States, according to Szilard, decided against that course for fear the first bomb might not go off.

During this recitation I was acutely aware of my Japanese guests. All three are small-boned and delicate, with soft voices. They sat together so the Nobel Prize-winning elder could translate. The younger ones listened with a kind of stoic acceptance of their avoidable tragedy. (Not I. I had never heard this before.)

Their concern, though, however gently put, over further nuclear testing, like the Bikini Atoll one which injured their fishermen and put radioactive tuna on Japanese tables, is vivid. Tomonaga said, “Hiroshima was a tragedy, but anti-Americanism is not so strong as fear of the results in radioactivity from tests.” One committee here focuses on radiation hazards - from testing and from an all-out war. I’ll be interested to see if the testers agree with the tested-upon; everyone seems to be testing near the Japanese islands.

I have helped Lacassagne translate his paper, since we discovered that my French is about on a par with his English. He is the expert on radiation. In elegant sentences he outlines the effect of strontium-90- The tests over the last six years will be responsible for an increase of 1 percent over the natural incidence of leukemia and bone cancer during the next few decades-about 100,000 additional cases. Global fallout from tests will produce genetic mutations over several generations among about the same number of people. Radiological hazards in a general war would be thousands of times greater: hundreds of millions killed outright by the heat blast and by the ionizing radiation at the instant of explosion, and additional hundreds of millions doomed by the delayed effects of radiation, some in succeeding generations as a result of genetic effects.

It is stated on good authority that a bomb can now be made which will be 2,500 times as powerful as the one that destroyed Hiroshima. It is feared that if many H-bombs are used there will be universal death -- sudden only for a minority, but for the majority a slow torture of disease and disintegration.

Everyone agrees that our Athens-Sparta spiraling situation must be broken. Another committee will address itself to that. Szilard wants to make the present stalemate “stable.”

The third committee deals with the responsibility of scientists. I was much impressed by these sober men; there are no ideological soap boxes. I am learning more than I want to know about, in Russell's words, “the tragic situation which confronts humanity whose continued existence is in doubt..” It is one thing to hear or read such a statement, and quite another to have it documented on a blackboard.

I. Ogawa and two other Japanese delegates.

The blackboard is in the two-storied Masonic Hall which is adorned solely by stained glass borders on its four front windows, and a bull's eye over the door. Since the room is used for a nursery school in winter, the blackboard crammed with the equations of disaster has a border of birds and flowers. There's a U-shaped table with kitchen chairs from all over Pugwash.

Now it’s all over. Our friends have departed-not the captains and the kings, unfortunately, just politically-powerless scientists who agreed, and said so, in a splendid statement warning the governments of the world that another war could lead to the annihilation of mankind. The final statement was adopted by all but Foster of Canada, and Szilard, who lived up to his reputation for refusing to agree with a majority on anything, even a proposal of his own. He abstained, after helping to prepare the statement.

When you consider the political tension and distrust between East and West, a statement that goes into detail on controversial issues and speaks of the responsibility of scientists is a sort of miracle. It had its anxious moments-different opinions, East and West, even on technical points like evaluating radiation hazards. The three committees worked hard and late, and apparently the readiness to accept a sound argument, plus their respect for scientific integrity and, maybe most important, that they represented only themselves, avoided a break-up.

Now it’s all over. Our friends have departed-not the captains and the kings, unfortunately, just politically-powerless scientists who agreed, and said so, in a splendid statement warning the governments of the world that another war could lead to the annihilation of mankind. The final statement was adopted by all but Foster of Canada, and Szilard, who lived up to his reputation for refusing to agree with a majority on anything, even a proposal of his own. He abstained, after helping to prepare the statement.

When you consider the political tension and distrust between East and West, a statement that goes into detail on controversial issues and speaks of the responsibility of scientists is a sort of miracle. It had its anxious moments-different opinions, East and West, even on technical points like evaluating radiation hazards. The three committees worked hard and late, and apparently the readiness to accept a sound argument, plus their respect for scientific integrity and, maybe most important, that they represented only themselves, avoided a break-up.

But it was Cecil Powell who made the public statement possible. He chaired the sessions that produced it from the three committee reports. His fairness, tact, patience and ability to grasp and restate varieties of viewpoints so that every man felt his opinion had been understood, appreciated, and considered was the real skin-of-the-teeth miracle. He is a true son of the Mother of Parliaments, a most admirable man for all seasons. Here's a quote to give you the cast of his mind: ”This is a decisive epoch of mankind. It is comparable to man's mastery of fire and the development of the scientific method by Leonardo and Bacon. No one can predict where the rapid progress of science and technology will lead us.“

Another great catalyst is Eugene Rabinowitch. His paper on the responsibility of scientists to “consider the implications of their own work was the basis for eleven points agreed on by everyone. Furthermore he speaks English, Russian, German, and French and sooner or later acted as interpreter for everyone else, even me. He began that chore at the first dinner when Cyrus asked him to say that although Nova Scotia is a poor province its supply of firewood is large and he hoped the guests would use their fireplaces as often as desired. Rabinowitch said this in three languages, rapidly, without even shifting gears. He, too, is articulate, as you know from his Bulletin articles. For instance: “the possibility of self-destruction in a nuclear war is not a passing emergency but will remain with mankind for all its future.”

At the last dinner, last night (lobster and champagne) he was the roving interpreter as each participant toasted the host and each other and pledged to work for peace. Lacassagne is such an actor that he really needed no interpreter although be spoke in French. He described his problems at a Paris travel agency when he asked for transportation to ”Poog vash” which no one had heard of or could locate on a map. ”Now,” he said, “Pugwash will go down in history with the great place names.” He gazed dramatically at a far point on the ceiling and said: ”Waterloo, Austerlitz et Pugwash.”

At the last dinner, last night (lobster and champagne) he was the roving interpreter as each participant toasted the host and each other and pledged to work for peace. Lacassagne is such an actor that he really needed no interpreter although be spoke in French. He described his problems at a Paris travel agency when he asked for transportation to ”Poog vash” which no one had heard of or could locate on a map. ”Now,” he said, “Pugwash will go down in history with the great place names.” He gazed dramatically at a far point on the ceiling and said: ”Waterloo, Austerlitz et Pugwash.”

Chou and Cyrus have talked a great deal about iron and steel. China is turning out a surprising amount of steel in sort of backyard furnaces. In answer to a direct question from Rotblat he said that China does not have the bomb “yet”; it is too busy with reconstruction. He said the Chinese want to abolish war; they have suffered too much. He called the Hiroshima bomb “murder” because, he said, most of the Japanese army was in northeast China where the Russians had crushed some of it and the People‘s Army had ”engaged” in it. He said the “stable stalemate” is inconceivable; it will be broken by new weapons and by more countries who will produce the bomb. Any country willing to spend the resources can have the bomb, he said.

That ”delicate strategic balance” is described in the statement as the greatest peril to mankind because it makes “any solution seem to be the advantage of one or the other disputant.” This was from the one committee (on the control of nuclear weapons) that concluded that the problem was too complex and controversial for it to make specific proposals.

That ”delicate strategic balance” is described in the statement as the greatest peril to mankind because it makes “any solution seem to be the advantage of one or the other disputant.” This was from the one committee (on the control of nuclear weapons) that concluded that the problem was too complex and controversial for it to make specific proposals.

I had a good-by drink with the Soviets; they gave up their cautious ginger ale some time ago (and brought out a huge supply of vodka and caviar as a gift). They are gratified by their experience here, especially that they have found the other scientists are men of good will who are as concerned as they are. Although they see eye to eye (more useful Russian vocabulary) with all the others in all instances, they now understand some of the reasoning behind the differences.

My good friend (more vocabulary) Topchiev says the Russians have always advocated greater exchanges of information and views, and “it is very important to find some agreement on the dangers of atomic war. It's a good beginning for future meetings. I believe scientists must meet and they must educate the peoples of the world that there must not be war.”

My good friend (more vocabulary) Topchiev says the Russians have always advocated greater exchanges of information and views, and “it is very important to find some agreement on the dangers of atomic war. It's a good beginning for future meetings. I believe scientists must meet and they must educate the peoples of the world that there must not be war.”

When he presented a stunning enamel-on-gold tea service in a satin-lined box, he said: “We have a saying that if you drink tea from a Russian cup, you will understand the Russian people. We have brought the cups but you have provided the tea. We thank you. We hope you will visit our country.”

As I said, we have met the Soviets and they are ours, but to be perfectly candid, I am theirs as well. Topchiev is a dear kind of man whom you would so enjoy; great warmth and sensitivity to people and situations, a grand eye for the ridiculous and a wit to match, but a gentle one befitting a man hounded by the specter of another war, further suffering for his country. He is a teddy bear of a Russian. When I asked him to tell me how to say ”I like you,” as we parted he felt honor bound, apparently, to explain that like and love are the same verb. When I said I was willing to risk that ambiguity in order to go on record about the finest croquet partner of my career, he said he was too. So my last vocabulary lesson was “I love you” and “I too.”

I must mention the marvelous change of atmosphere here as though early on these men decided that although they might not trust each governments, they could trust each other. When I mentioned this to Leo Szilard, he said, “Hah! Who trusts his own government let alone someone ekes?” Nevertheless, Szilard feels the urgency as the other experts do of issuing this warning to the governments of the world.

Sitting in the back of the Masonic Hall, taking notes and hearing this urgency in the voices of the experts, is an privilege from which I think I will never recover.

Anne Eaton

As I said, we have met the Soviets and they are ours, but to be perfectly candid, I am theirs as well. Topchiev is a dear kind of man whom you would so enjoy; great warmth and sensitivity to people and situations, a grand eye for the ridiculous and a wit to match, but a gentle one befitting a man hounded by the specter of another war, further suffering for his country. He is a teddy bear of a Russian. When I asked him to tell me how to say ”I like you,” as we parted he felt honor bound, apparently, to explain that like and love are the same verb. When I said I was willing to risk that ambiguity in order to go on record about the finest croquet partner of my career, he said he was too. So my last vocabulary lesson was “I love you” and “I too.”

I must mention the marvelous change of atmosphere here as though early on these men decided that although they might not trust each governments, they could trust each other. When I mentioned this to Leo Szilard, he said, “Hah! Who trusts his own government let alone someone ekes?” Nevertheless, Szilard feels the urgency as the other experts do of issuing this warning to the governments of the world.

Sitting in the back of the Masonic Hall, taking notes and hearing this urgency in the voices of the experts, is an privilege from which I think I will never recover.

Anne Eaton

Joseph Rotblat pictured here with Ruth Adams dedicated the rest of his life to pursue the end of nuclear proliferation and to work towards a world where people from all countries could co-exist peacefully.

Anne returned to Cleveland and married Cyrus Eaton December 20, 1957.

Twenty-five years after the conference, Anne Eaton said, "This experience and this education galvanized Cyrus and me in the kind of activity that we started immediately."

Twenty-five years after the conference, Anne Eaton said, "This experience and this education galvanized Cyrus and me in the kind of activity that we started immediately."

Friendships were forged, and conversations were started that would continue for decades.